|

|

AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAThursday, August 14, 2014 The Pacific tuna industry has joined environmental organisations and scientists calling for serious action to save bigeye tuna. More than 60 per cent of the world's tuna is caught in the Pacific, much of it by powerful distant water fishing nations from Asia, Europe and North America. Scientists meeting at the region's tuna management body, the Central and Western Pacific Fisheries Commission, have heard bigeye tuna stocks are down to just 16 per of the original population. Source: Radio Austalia |

Showing posts with label JAPAN TUNA TRADE. Show all posts

Showing posts with label JAPAN TUNA TRADE. Show all posts

IN BRIEF - Pacific tuna industry calls for 'drastic' action to avoid bigeye stock collapse

Fishing Vessel - 1999 Ex Tuna Longliner

This 1999 fishing vessel is no longer needed by the owner, and they would like to sell the unit in an asset liquidation sale. The unit needs prevention repair.

Details:

- FFS341-1999 – Fishing vessel/freezer

- Bbuilt 1999, Taiwan

- IACS class,SS due July, 2015

- Intermediate survey passed in 2012

- Sailing region unlimited

- GRT 708/341 T

- L 56,18 m, B 8,6 m, D 3,75, DWT 341 t, draft 3,4 m

- Speed 12 knots, M/E Japanese maid Akasaka

- 1 x 1150 KW

- Freezing plant Hasegawa, freon R22, 4 x compressors

- Frozen fish output upto 40 t/day

- Temperature in holds –25 degrC, 5 reefer holds

- Capacity 379 CBM, hatches dims 2 x 2 m, stern & bow

- Thrusters fitted

- Hydro location station Wesmar-850

- Sailing range 60 days

- Crew 35 berths

- Vessel is fitted with side fishing traps for saury fishing

agencia.marinero@gmail.com

Bluefin Tuna Aquaculture Business Operated by Nissui

Headquartered in Kagoshima Prefecture, Nakatani Suisan Co., Ltd.

engages in Bluefin Tuna aquaculture as a Nissui Group company. Nakatani

Suisan purchases young fish caught in July and August from fisherman

operating in the Pacific Ocean off the Shikoku and in the Sea of

Japan off the Oki Islands. These young fish are then given feed

in taming fish cages set in Shikoku and Oki for about two months

until they weigh about 500g to 1kg; they are then transported to

farming fish cages set in each region in live fish vessels.

The farming fish cages are set in Amami, Kagoshima Prefecture; Koshikijima, Satsumasendai City, Kagoshima Prefecture; and Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture. The main cages are those in Amami and Koshikijima. In particular, Amami is a mecca for Bluefin Tuna aquaculture, where many companies including Nakatani Suisan set fish cages; it is also where half of the Bluefin Tuna produced through aquaculture in Japan is harvested. In Koshikijima, Nakatani Suisan is the exclusive operator of the Bluefin Tuna aquaculture business under a highly trusting relationship with the fishermen's cooperative. The company can also enjoy the advantage that young fish of Bluefin Tuna can be caught in the surrounding sea.

Grown Bluefin Tuna are caught from the fish cages one at a time; then, their blood, gills and guts are removed at sea in just 1 to 2 minutes, which ensures the constant freshness of fish. After the Bluefin Tuna are transported in an ice water tank to a harbor processing plant, basic data such as length and weight is taken. Upon inspection, the raw fish are immediately put into ice-filled boxes and transported to Kagoshima Airport and flown to various cities across Japan. Traceability is ensured by recording the production and transportation history for each fish. After purchasing the whole amount of safe, great-tasting Bluefin Tuna from Nakatani Suisan, Nissui distributes one half of the total amount to the market through wholesalers, while it processes the remaining half in Narita for shipment to mass merchandisers. In this way, Bluefin Tuna that were farmed for over 2 to 3 years are placed to tables at restaurants and at home in merely 3 days. |

OPRT-Organization for the Promotion of Responsible Tuna Fisheries

Why was the OPRT created?

Japan is the only country in the world where eating sashimi tuna is an inherent part of the food culture. Of course, other countries utilize canned tuna; however, the selling price for sashimi tuna is 10 to 30 times higher than that of canned tuna.

Sankaido Bldg. (9th Floor)

1-9-13 Akasaka, Minato-ku

Tokyo 107-0052 Japan

Tel: 03-3568-6388

Fax: 03-3568-6389

Japan is the only country in the world where eating sashimi tuna is an inherent part of the food culture. Of course, other countries utilize canned tuna; however, the selling price for sashimi tuna is 10 to 30 times higher than that of canned tuna.

For this reason, the fishing for sashimi

tuna has expanded rapidly and extensively. Fishing vessels not only from

Japan but from the rest of the world are capitalizing on this trend.

All tunas caught worldwide for sashimi are sold to Japanese market.

In 1999, the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations (FAO) warned of the need to decrease

the number of tuna vessels, since most of the tuna stocks throughout the

world had been fully or overly exploited.

Japan holds a great responsibility for the

situation with the world’s leading market for sashimi tuna, and, with

this fact in mind, the OPRT has been created. It has started

activities sure to help promote the proper conservation and management

of tuna stocks for people all over the world.

OPRT Contact

Organization for the Promotion of Responsible Tuna FisheriesSankaido Bldg. (9th Floor)

1-9-13 Akasaka, Minato-ku

Tokyo 107-0052 Japan

Tel: 03-3568-6388

Fax: 03-3568-6389

BLUEFIN TUNA AND JAPAN

magaro hunks on

sale in Tsukiji More than 80 percent of the global bluefin tuna catch is consumed in Japan. Bluefin imports increased from 340 tons in 1970 to more than 20,000 tons in 2008, with Japanese trading firms often purchasing a vessel’s entire catch. Consumption reached 44,000 tons in 2006 with domestic production accounting for less than 15,000 tons. Japanese consume more 25 percent of the world’s catch of all species of tuna. Not surprisingly Japan is the world’s largest importer of tuna. It imported 36,989 tons in 2005.

About 1,200 fishing

boats engage in oceangoing, long-line tuna fishing worldwide. Ninety

percent of these are from Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan. These

vessels often stay out at sea for about a year, conducting only a couple

of catches during that time.

In January 2009, the

Japanese government said that its longline tuna fleet would be cut by 10

percent to 20 percent in response to higher international restrictions

on tuna catches. The number of ocean-going vessels would be reduced from

390 to between 310 and 380 ships. The number of coastal vessels would

be reduced from 349 to between 300 and 310 ships. The move is expected

to result in the loss of 1,000 jobs and raise the price of tuna.

In January 2011, a 342-kilogram bluefin tuna was sold at Tsukiji for a

record price of ¥32.49 million ($360,000). The was caught off Toi,

Hokkaido and fetched such a high rice because of its quality and

freshness and the fact that bad weather reduced the New Year catch (538

bluefin were auctioned off, 33 fewer than the year before). The

record-breaking fish was purchased jointly by Kyubei, a famous sushi

restaurant in Ginza, and Itamae Sushi, a chain of restaurants in Japan

and Hong Kong.

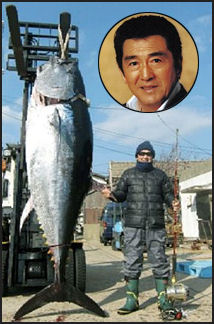

In July 2010, the largest bluefin

tuna caught since 1986 was sold at Tsukiji. The 445-kilogram fish, which

was weighed after it had been gutted and cleaned, was caught off

Nagasaki Prefecture in Japan. It was auctioned off for ¥3.2 million (

¥7,200 per kilogram). The largest bluefin tuna every sold at Tsukiji was

a 496-kilogram fish caught in April 1986. The biggest bluefin ever

caught was a 497-kilogram Canadian fish caught in 1995.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: FISHING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISHING AND JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TSUKIJI FISH MARKET IN TOKYO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TRADITIONAL FISHING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PEARLS AND JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SEAFOOD IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUSHI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUGU (BLOWFISH) IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources on Fishing: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries maff.go.jp/e ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Fisheries Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Blue Fin Tuna Fishing : Northern Blue Fin Tuna fishbase.org ; Southern Blue Fin Tuna fishbase.org ; Wikipedia article on Blue Fin Tuna Wikipedia ; Blue fin Tuna Fishing Methods content.cdlib.org ; Mediterranean Blue Fin Tuna Aquaculture eeuropeanrussianaffairs.suite101.com ; Southern Bluefin Tuna Aquaculture sardi.sa.gov.au/aquaculture ; Blue Fin Tuna Farming Off Spain uni-duesseldorf.de

Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo : Tsukiji Market site tsukiji-market.or.jp ; Essay on Tsukiji aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Tsukiji Research people.fas.harvard.edu ; Japan Guide japan-guide.com Getting There: Best Japanese Sushi google.com/site/bestjapanesesushi ; Photos: Tsukiji Tour http://homepage3.nifty.com/tokyoworks/TsukijiTour/TsukijiTourEng.htm

Traditional Fishing in Japan: Ama Divers thingsasian.com ; Ama Physiology archive.rubicon-foundation.org ; Amasan hanamiweb.com ; Squid Fishing jtackle.info/squid ; Cormorant fishing Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Cormorant fishing in Yangshuo yangshuo-travel-guide ; Photos of Cormorant fishing molon.de ; Articles on Cormorant Fishing highbeam.com

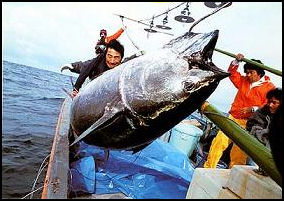

Catching Blue Fin Tuna

In Japan, bluefin tuna tend to be caught using the rod-and-line technique or long lines. In the Atlantic they are often caught with spotter planes and harpoons that electrocute the fish dead with hundred of volts of power. Favored fishing places include the Mediterranean, near the Azores and the waters off Boston.

The

bluefin tuna season in Cape Cod begins in late June when the fish

migrate to the North Atlantic. Spotter planes used to find tuna

generally get 25 percent of the money from the sale of the fish.

Electric harpoons are preferred for killing the tuna because fish that

are caught with a line fight for a long time, which raises their body

temperature and produces an unwanted flavor called ya-ke.

Immediately after being caught and brought on

board bluefin tuna are gutted, instantly frozen at -76̊F and put in

coffin-like containers packed with ice and often transported later that

day via cargo jets to Japan. Even fish caught by sport fishermen often

end up in Japan. Japanese wholesalers have contacts at sport fishing

dock in Miami and other places.

At many ports where blue fin are brought, "tuna techs" from Tsukiji educate American fishermen about the tuna's kata , or ideal form, and what to look for in color, texture, fish content and body shape. .

Tuna Caught in the Tsugaru Strait

The best bluefin tuna caching grounds in Japan are said to be in the Tsugaru Strait off Omamachi in Aomori Prefecture in northern Honshu. Bluefin tuna unloaded at the port in Omamachi are known as Oma Maguro. They tend to sell for double the price of tuna caught elsewhere.

The best bluefin tuna in the Tsugaru Strait are

caught during the winter when the waters in the strait are rich in small

fish eaten by tuna and it is not unusual for tuna weighing 300

kilograms or more to be caught.

Bluefin tuna are particularly valuable at that

time of year because the are rich in fat and tuna supplies worldwide

tend to decline in the winter. Fishermen risk their lives going out in

the rough seas to catch tuna. Some lose fingers after getting them

caught in fishing lines while trying to pull in large fish. One

fisherman told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “In winter, I go out fishing even if

the wind is blowing 70 kilometers per hour because its worth the

danger.”

There is conflict there between fishermen using

the rod-and-line technique and other who use long lines. In recent years

as the price of bluefin tuna has risen and cost of fishing have

increased, long line fishermen have intruded on fishing grounds reserved

for rod- and-line fishing. The long lines are sometimes 3,000 meters

long. Not only do conservation oppose the method other fishermen don’t

like them because the long lines can become entangled created a mess in

popular fishing areas.

Penalties of one year in prison and ¥500,000 fines

for repeated violations don’t do much to deter the long line fishermen.

There have been cases where long line boats have been chased and

surrounded by rod-and-line boats who cut the lines of the long-line

fishermen.

In January 2010, a 232.6-kilogram bluefin tuna was

sold at Tsukiji for ¥16.28 million (about $175,000), or ¥70,000 a

kilogram. The fish was caught off Oma-machi, Aomori Prefecture.

Declines, Quotas and Prices on Blue Fin Tuna

By some estimates bluefin tuna stocks have

declined 80 percent. The number of mature Atlantic bluefin is thought to

have dropped from 250,000 in 1970 to 100,000 in recent years.

The decline in tuna numbers has been blamed

in part on the use of roll-net equipped fishing boats that scoop up

large volumes of fish in one swoop. Greenpeace and other environmental

organizations have become increasingly critical of the bluefin trade and

many sushi restaurants in Europe don’t serve the fish.

In the old days there were so many frozen bluefin

tuna at Tsukiji’s auction they had to be stacked on top of each other.

That is no longer the case. One wholesale fish buyer told the Washington

Post. “We were too loose in governing our own fishing. We now need a

very rigid regimen to show the world we can control ourselves. Instead

of eating tuna twice a week, the Japanese are going to have to settle

for twice a month...We all have to share what we have got. If we do

that. I don’t think they are going extinct.”

Quotas on Blue Fin Tuna

Whenever there is talk is a shortage or

overfishing of tuna eyes are inevitably cast towards Japan. The catch

quotas of bluefin tuna in the late 2000s was 23,900 tons for Atlantic

bluefin tuna in 2009, 24,900 tons for Pacific bluefin tuna in 2008, and

11,800 tons for southern bluefin tuna in 2009.

Five regional fishery control organizations

control (or at least try to control) tuna fishing worldwide. The

International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT)

is responsible for fish caught in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

ICCAT's quota was 13,500 tons in 2010, down from 20,000 tons in 2009.

Japan’s quota for southern bluefin tuna was 6000

tons in 2006. According to a group called the Commission Conservation of

Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), Japan caught more twice the amounts of

southern bluefin tuna that was allowed to catch between 2003 and 2005.

Japanese fishermen said they just exceeded their quotas of 6,000 tons a

years but based on the amounts sold the CCSBT estimated that between

10,000 to 16,000 tons were actually caught.

As punishment for overfishing the CCSBT halved

Japan’s quota to 3000 tons. The government Fisheries Agency admitted

that bluefin tuna was overfished and agreed to have the annual quota to

3,000 tons for five years beginning in 2007. There were worries the

move might set off price hikes.

Japan’s quota for Atlantic bluefin is about a

quarter of what it was. In November 2006, Japan took the unusual step of

voluntarily agreeing to cut its quota of Atlantic tuna in part to head

more severe imposed cuts.

The cuts and quotas are not expected to affect the

supply or price of tuna by that much and many hope they will lead to

more responsible fishing. The price of bluefin tuna rose 20 percent in

Tokyo in 2007. In many case sushi restaurants have not been able to pass

on the costs to their customers and take a loss whenever their

customers eat too much bluefin sushi. High prices have caused household

consumption of blue fin tuna to decline 20 percent.

Limits on Bluefin Tuna

The global bluefin tuna catch was cut by 39 percent in 2010 from the

previous year to 11,500 tons with Japan’s total catch reduced to 1,148

tons.

In 2010: 1) the international cap on Pacific

bluefin went into effect the permits caches at 2002-2004 levels; 2), the

catch quota for bigeye tuna was reduced 30 percent for three years; and

3) and the regulations for Atlantic Ocean fishing looked likely to be

further tightened. At some bluefin market sales only 1 percent of the

fish on sale had been caught at sea. The rest had been farmed.

In November 2009, there were rumors that there

might be shortages of bluefin tuna during the holiday season and that

prices for the fish were going to spike. The government issued a

statement that the rumors were not true and that suppliers stockpiled an

ample supply.

At the first bluefin auction of the year at Tsukiji

in 2010, there were 20 percent less fish than at the same time a year

earlier. One wholesaler told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Since the first

auction of the year, few tuna have been up for auction. Prices are up 20

percent on last year. I hope it’s not a bad sign.” An executive with a

fishing organization said, “If catches and stockpiles decrease, and the

economy recovers and demand increases, prices will rise.”

Limits on Mediterranean Bluefin Tuna

The International Commission Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) has

called for a 38.6 percent cut in the annual catch of Atlantic bluefin

tuna in 2010, the biggest ever decrease.

An estimated $4.5 billion worth or unreported,

illegal catches have occurred in the Mediterranean during the 2000s,

with much of the catching ending up in Japan. ICCAT estimates that the

amount of Atlantic bluefin tuna actually caught is double the catch

limits. In 2002, for example, the catch limit in the Atlantic and

Mediterranean was 32,000 tons but ICCAT believes that 50,000 tons was

actually caught. Such large amount are illegally caught because fishing

nations refuse to set standards and procedures that could address the

problem.

Roberto Bregazzi, a tuna industry analyst, has

called the practice “intolerable tax free looting” and estimated the

amount of illegally-caught tuna rose from 3,569 tons in 2004 to 24,297

tons in 2008. He told the fishing trade journal Interfish, “Thanks to a

new generation of ultra-low freezing technology, Japanese fresh and

frozen tuna traders are no longer faced with the urgency of its rapid

market distribution. Tuna has thus become a commodity with which Japan

can speculate.”

Proposed Bluefin Tuna Ban

In March 2010, a proposal to ban the export of

Atlantic bluefin tuna by declaring the fish an endangered species failed

to become enacted at a meeting of the 175-nation Convention on the

International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

(CITIES), also known as the Washington Convention, in Doha, Qatar. For a

while it looked as if the Monaco-introduced proposal was going to pass.

It was supported a United Nations conservation organization, the United

States, the European Union, France, Italy and several European

countries. On the eve of the vote bluefin tuna prices rose to ¥6,500 a

kilograms, compared to ¥4,000 a couple months earlier. But in the end

only 20 nations vote in favor of the ban while 68 voted against it, with

30 abstentions. A two thirds majority was needed for the measure to be

passed.

It was a novel idea to try and restrict the

bluefin trade using CITIES, which was set up to protect endangered

species. Normally fishing matters are handled by fishing organizations

like the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas

(ICCAT). Supporters of the ban claimed bluefin tun were “on the verge

of extinction.” Among the arguments used against the ban were that it

hurt fisherman in developing nation and labeling bluefin fin endangered

was not scientifically justified. In the end many countries chose to

vote against the ban as economic concerns prevailed over conservation.

Traders were relieved by the decision but

environmentalist were worried about the future of bluefin tuna and the

sustainability of the catch.

Bluefin Tuna Stockpiles and Sales

tuna buyer in Greece Bregazzi claims that 47,000 tons of tuna has been stockpiled in Japan as of June 2009 in the anticipation that tuna fisheries will become depleted enough to send the price of tuna through the roof. In Japan, tuna are stored for long periods in warehouses where temperatures are kept at -60 degrees C. The stockpile of bluefin tuna in freezers across Japan is said to be enough to last for between a year and 18 months. Such huge stockpiles of tuna lead to prices of tuna falling by 10 percent in 2009 while there was talk of tuna going extinct.

Bluefin tuna caught off New England is sold at the

docks to Japanese buyers who grade the fish for freshness color, fat

and shape and offer prices based on the going rates at Tsukiji fish

market in Tokyo that day. The purchased fish is packed in ice,

transported to the airports and loaded on Japan Airlines planes at New

York's Kennedy Airport for a 15 hour flight to Tokyo, where a single

tuna can cost $80,000.

Describing the scene at a pier in Bath, Maine,

Theodore Betsor wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, "After 20 minutes of eyeing

the goods, many of the buyers return to their trucks to call Japan by

cellular phone and get the morning prices from Tokyo's Tsukiji

Market...The buyers give written bids to the dock manager, who passes

the top bid for each fish to the crew that landed it."

"Each secret auction bid is examined anxiously by a

cluster of young men. After a few minutes deals are closed and the fish

are quickly loaded onto the backs of trucks in crates of crushed ice."

American fishermen usually get around $10 to $20 a pound on the docks

for bluefish catches.

Japanese imports of fresh bluefin tuna worldwide

increased from 957 tons in 1984 to 5,235 tons in 1993. The price peaked

in 1990 at $34 per kilogram when a typical 350 pound fish sold for

around $10,000. As of 2008, bluefin was selling for $23 a kilogram.

Higher prices are charged for really high quality fish.

Selling Blue Fin Tuna in Japan

magaro at the fish auction at Tsukiji See Tokyo's Tsukiji Market,

Bluefin tuna worth over a $150,000 have been sold

at Tsukiji. In 2001, a 202-kilogram tuna caught in Tsugaru Straight near

Omanachi I Aomori Prefecture sold for a whopping $173,600 or about $800

a kilogram.

In recent years prices have come down. Bluefin

tuna was selling for ¥3,000 a kilogram in 2008, compared to ¥4,500 a

kilogram in 1989. See Living, Food

More and more the amount bluefin tuna available on

a given day is unreliable and buyers are relying more and more on large

commercial freezers to store supplies so they don’t run out. Tuna

frozen with the special “flash” method can be kept for up to a year with

no perceivable change in taste.

Single Bluefin Tuna Sold for Record $736,500

In January 2012, AFP reported: A deep-pocketed

restaurateur shelled out nearly $750,000 for a tuna at Japan's Tsukiji

fish market, smashing the record price for a single bluefin. The

269-kilogramme (592-pound) fish -- caught off the coast of Japan's

northern Aomori prefecture -- stood at an eye-popping 56.49 million yen

($736,500) when the hammer came down in the first auction of the year.

The figure dwarfs the previous high of 32.49 million yen paid at last

year's inaugural auction at Tsukiji, a huge working market that features

on many Tokyo tourist itineraries. [Source: Yoshikazu Tsuno, AFP,

January 5, 2012]

The winning bidder was Kiyoshi Kimura, president

of the company that runs the popular Sushi-Zanmai chain. At around

210,000 yen per kilogramme, a single slice of sushi could cost as much

as 5,000 yen, but the firm plans to sell it at a more regular price of

up to 418 yen, local media reported. "The flesh is coloured in

magnificent red and the quality of fat is very good," Kimura said. "It

is very delicious. The taste is unbeatable." A Hong Kong sushi

restaurant owner bought the previous year's record tuna, and Kimura

added: "I wanted to win the best tuna so that Japanese customers, not

overseas, can enjoy it."

Emiko Misumi, a 44-year-old woman who tasted a

slice, said: "This tuna is so fatty and very delicious." "It was sweet

even without sugar or sake. It was a very delicate sweet taste," said

another female customer Noriko Nakai, 63.

Farming Bluefin Tuna from Eggs in Japan

The Japanese are experimenting with raising bluefin tuna in huge ocean

enclosures. Researchers from Kinki University are raising bluefin in

circular pens, about 70 meters across, in waters off Kushimoticho,

Wakayama. After the fish reach a length of one meter and weight of 30

kilograms and their fat content is high enough that can be sold

commercially. Some reach a weight of 350 kilograms. The tuna are fed

squid and mackerel.

In 2009 Kinki University researchers hatched about

190,000 bluefin tuna eggs, of which about 40,000 grew to be fingerlings,

This figure was impressive but still meant only 0.5 percent of the eggs

survived, About 60 tons of bluefin tuna meat was produced. Branded Kindai maguro (“Kinki University tuna”), it has a higher fat content than fish caught in the wild.

In June 2002, a team at the Kinki University

Fisheries Laboratory led by Professor Hidemi Kumai became the first, to

artificially breed bluefin tuna fry from to artificially incubated

mature tuna. More than 5,000 eggs were produced by six 7-year-old tuna

and fourteen 6-year-old tuna, all of born and raised in captivity.

About 160 of the bluefin tuna that hatched in 2002 were still alive in

2006. On average they were about 1.2 meter long. and weighed about 70

kilograms.

Kinki University researchers have also had success

raising kelp grouper and burhura, a hybrid species created by

crossbreeding Japanese amberjack and goldstriped amberjack. The

laboratory hopes to make ¥2 billion a year from selling fish it

produces. It sells both fry to fish farmers and fresh fish that are

marketed as being safe and high quality. The university successfully

bred more that 20 types of fish, including red sea bream, bastard

halibut, rock progy and amberjack in the late 1960s.

History of Fish Farming Tuna

The team at Kinki University was able to get tuna to produce fertile

eggs in 1979 but all the eggs and fry died within a few weeks. When the

tuna spawned again in 1980 and 1982 the fry were kept alive for up to

57 days. The tuna did not spawn again until 1994 and the spawned five

times between 1994 and 2001.

In the meantime scientists learned that big fry

are smaller fry and this led to a separation of fry by size. In 1994,

1800 two- to three-month-old fry were released into sea pens. But a

month later all but 40 were dead. One lived for 246 days and reached a

size of 1.3 kilograms. The team concluded that the fish died because the

pens were too small and replaced the six-meter square pens with

12-meter octagonal pen made of synthetic fibers. The one-month survival

rate increased to 16.4 percent in 1995 and 24.9 percent in 1996.

Because young fish can travel fast but can’t turn

so well they often collide with net sides of their pens until they are

25 centimeters in length. In 1998 the team developed a circular pen that

was six meters deep and 30 meters in diameter. In this pen the

one-month survival figure was 55.7 percent. About 400 survived in the

pen for more than twp years. The Kinki University team also found that

the tuna are very sensitive to light and noise and reacted negatively to

the presence of cars traveling near their pens.

Clean Seas Tuna, a company based in Port Lincoln

Australia, has invested ten of millions of dollars to hatch tuna from an

indoor hatchery at the hamlet of Arno Bay 120 kilometers north of Port

Lincoln. Here large bluefin tuna are kept in a massive tank that tries

to fool the fish into thinking they have reached their spawning grounds

by simulating ocean currents, increasing the temperature of the water in

their tanks and the amount of light. In March 2008, the company

announced a major breakthrough: it collected its first batch of

fertilized eggs from a breeding stock of about 20 tuna weighing 160

kilograms.

Clean Seas Tuna has gotten its bleeding stock to

spawn several times and produce eggs and larvae but is still working out

how to feed and care for the larvae. Many investors are skeptical that

Clean Sea will achieve its goal of raising bluefin tuna captivity and

say even if they do the cost will be too high to turn a profit. The fish

only grow at a rate of one kilogram a month The attraction for Clean

Seas is that it will be able to sell tuna without any quotas restricting

the company. It hopes to sell 5000 tons year, with its first sales in

2009.

In September 2009, researchers with the Fisheries

Laboratory at Kinki University, in Shirahama Wakayama Prefecture and

Australia-based Clean Seas Tuna announced they had succeeded in breeding

southern bluefin tuna and produced bluefin tuna fry, a step which could

open the way to commercial cultivation of bluefin tuna.

Bluefin Tuna Farming Details

Researchers at Kinki University predict that

Japan should be able to produce 100 percent of domestic demand for

bluefin tuna with farmed fish raised from eggs rather than caught in the

wild. In this process: 1) eggs about 1 millimeter is diameter are

fertilized; 2) After about 35 hours three-millimeter fish are

artificially hatched and fed on plankton for 15 to 20 days; 3) three- to

five-centimeter-long fry eat hatchling parrot bass and other fish for

two to three months; 4) 20 to 30-centimeter-long fingerlings eat process

for feed for more than four years; 5) mature fish are one meter to one

and half meters long.

The pens need to be at least 10 meters deep and 30

meters in diameter so that fish do not collide with nets. The pens need

to be away from human activity as they are easily panicked by things

like car lights and noise from fireworks, with some injuring themselves

by crashing into their nets at high speed. The fish are also vulnerable

to to poor water conditions created by typhoons. Night lighting is used

to accustom young fish to light.

Bluefin tuna are regarded as particularly

difficult to cultivate because of their sensitivity to conditions when

laying eggs.. The fish will not lay eggs in temperatures below 26?C or

if it is too windy or rainy. Even if the eggs hatch they chance they

will becoming a six-centimeter-long fry is only 3 percent. There is only

a 0.1 chance the fish will reach a salable size and be sold in markets.

Even if they make it to adulthood, many die often panicking and

ramming into the net or side of the enclosure.

Farm raised tuna generally has a higher fat

content than wild tuna. The main expense of raising blue fin tuna is the

cost of food. A one meter tuna need about 15 kilogram of live fish to

put on one kilogram of fat, and abbout 1.5 tons to two tons of squid and

mackerel are needed to produce a 100 kilogram bluefin tuna.

Scientists are currently trying to develop less expensive fish feed.

One of main obstacles is her is creating a processed food that doesn’t

affect the taste of the tuna because what a tuna eats very much affects

the taste of its meat.

Prof. Kumai , who spent more than 50 years studying

bluefin tuna , told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “It could be possible to meet

world demand with farmed fish. In the future we’d like to try releasing

fish bred in captivity into the ocean. I’d love to see Kindau maguro

swimming around the globe.”

Bluefin Tuna Farms with Wild Fish

Fish farms, or fish ranches as they are sometimes called, for bluefin

tuna are places where fish corralled in the open sea are brought and

kept in giant underwater cages and fattened up with sardines and tuna

for between a few months to a year.

The technique, which is really more like rustling

than ranching, has revolutionized the bluefin industry. Fishermen scoop

up schools of spawning tuna and transfer them to 50-meter-wide cages and

return to the spawning area catching all the fish they can. The

practice is though to be particularly damaging to fish stocks because it

captures large number of fish at place they come to spawn. Not only are

large numbers of fish caught they are also deprived of producing

offspring

About 20 percent of the bluefin tuna consumed in

Japan is farmed from wild fish. About 400,000 bluefin tuna are being

raised on farms as of 2010. Sojitz exports farmed tuna from Japan to

China.

Because bluefin tuna swim so fast and are used to

migrating long distances they are difficult to keep in small pens. Their

delicate skin can be easily damaged if touched by human hands and to

much handling can be fatal.

Farming of bluefin tuna is common in the

Mediterranean. The practice began there in Croatia in 1996 and since has

then has begun in Italy, Spain and Turkey . In the Mediterranean the

tuna are caught in their spawning ground in waters off Libya. They are

transferred to underwater boxes and fattened up with fish meal,

sardines, mackerel and squid, up to two years, to increase the fatty

meat valued in Japan. According to a WWF report fish farming is

responsible for depleting stocks of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean

because so many spawning fish are caught. Japanese firms own a sizable

part of the bluefin tuna farm industry in the Mediterranean.

High-Tech Tuna Factory at Okayama University

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A "fish factory"

has been in operation for two years on the hilly campus of Okayama

University of Science in Okayama. The indoor facility is equipped with

water-circulation machines and other devices.The project is one of an

increasing number of attempts to introduce the latest science and

technology into primary industries to make the field more profitable.

[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 8, 2012]

“The one-story building holds large and small

aquarium tanks, including a round tank measuring eight meters in

diameter near one end of the building, where three bluefin tuna, each

weighing about eight kilograms, were swimming around. Toshimasa

Yamamoto, 53, an associate professor of the university's Faculty of

Engineering, said: "I want to establish technologies to enable fish

farming with high added value even in villages in mountainous regions

where depopulation or graying of the population is progressing. By doing

so, I want to create new industries.” [Ibid]

“He developed a method of adding small quantities

of sodium, potassium and other elements to freshwater so that both

saltwater fish and freshwater fish can be farmed in it. he method is

less costly than transporting seawater to mountainous areas and makes it

easier to control water quality. urrently, the fish-farming research is

under way with eight species of fish. Yamamoto has especially high

hopes for bluefin tuna, which are high-quality fish. [Ibid]

“Farming bluefin tuna is difficult because the

fish swim at high speeds, and are sensitive to light and sounds. Often

the fish crash into tank walls or jump out of the tank. In 2010, when he

first got the fish factory running, all the tuna died. Since summer of

last year, he has made some improvements to the facility. For example,

iodine, which has bactericidal effects, has been added to the water, and

nets to prevent fish from jumping out have been placed over the tank.

As a result, young 25-centimeter fish have grown to 80 centimeters in

eight months. [Ibid]

“If costs for circulating and purifying water can

be lowered, the fish will be more competitive in the market. Yamamoto

has received proposals for joint research from U.S., Chinese and South

Korean companies. He said, "An age in which agricultural cooperatives

will ship bluefin tuna may be coming.” [Ibid]

Tuna Farming in Australia

Bluefin fish farming began in Australia in the 1980s when quotas and

low prices threatened to bankrupt many operators. Fishermen there came

up the brilliant idea of netting their quotas and increasing their size

and profits.

Tuna fishermen in Australia operate under a quota

system. After overfishing seriously depleted tuna fisheries in the

1980s, fishermen were required to obtain an individual transferable

quota which gave them the right to catch a certain number of fish each

year. The quota system was great for the fishermen. Fisherman that once

earned $600 a ton selling fish to canneries began making more than

$1,000 per fish, selling them to buyers for the Japanese market. The

quotas are expensive. They are bought and sold like stocks.

Bluefin tuna farmed in Australia are caught in

nets during a two-week "round-up" and slowly towed to floating pens near

the shore. The tuna are fed and harvested when prices are high on the

Tokyo market. The fish are fattened up with pilchards and anchovies and

sold when they double in size to around 32 kilograms.

The 2,000 or so tuna kept in a single pen are

worth around $2 million. They are so valuable armed guards keep watch

over them. At harvest time the fish are gently guided into a boat (any

bruising lowers the price) and killed and flash frozen and put on

Tokyo-bound planes

Australia exports 10,000 metric tons of bluefin

worth $200 million. Almost all is from penned stocks. Australia and New

Zealand are concerned about potential overfishing of bluefin tuna in the

Southern Sea by Japanese ships.

Chikuyo Tuna

Tuna raised on the farms described above are known as chikuyo tuna.

One of the aims of the process is to increase the body fat on the fish. A

high fat contents means that up to 70 percent of the fish can be sold

as fatty, premium-priced toro (normally only 20 percent of a fish can be

sold as toro). But a lack of exercise leaves the flesh overly soft and

lacking in taste and texture.

Much of the toro sold in sushi bars is chikuyo

tuna. It cost about half as much as wild tuna and ths has brought down

the price of toro so that it can be enjoyed by ordinary consumers.

Oversupply has caused prices to drop even further. Now toro is available

for as little as ¥1,000 per kilogram compared to ¥5,000 per kilogram

that it sold for in the Bubble Economy era in the 1980s.

The lower prices have meant that the best quality

toro is now even available at conveyor belt sushi restaurants. Japan

imported about 3,000 tons of chikuyo tuna 1995 and 35,000 tons in 2005.

Chikuyo tuna is known for being

particularly fatty. When he first encountered the fish one sushi

restaurant chef told the Yomiuri Shimbun , “The tuna was like a big

chunk of fat. A real sushi lover would find the is tuna’s smell

different from the flavor of wild bluefin tuna.” The fish have more

fat and thus softer meat in part because they get less exercise swimming

around in small enclosed spaces that wild fish do in the open sea.

In wild bluefin tuna 30 percent to 40

percent of the fish excluding the head is classified as toro. In chikuyo

bluefin tuna the figures rises to 70 percent or even 80 percent.

Image Sources: 1) 3) Japan Zone 2) 4) Wikipedia 5) JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily

Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO),

National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely

Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other

publications.

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 13TH INFOFISH WORLD TUNA TRADE CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION

21 – 23 May, 2014

Shangri-La Hotel, Bangkok, Thailand

CHAIRPERSON

RENATO CURTO

PRESIDENT AND CEO OF TRI MARINE GROUP

CO-CHAIRPERSON

CHANINTR CHALISARAPONG

CHAIRMAN, THAI TUNA INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION

Tuesday, 20 May, 2014

17.00 – 21.00 Registration (Grand Ballroom)

Wednesday, 21 May, 2014 - Day 1

07.30 – 09.00 – Registration (Grand Ballroom)– Welcome address by Abdul Basir Kunhimohammed , Director, INFOFISH, Malaysia – Special address by H.E Mohamed Shainee , Minister, Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Maldives – Special address by H.E Mao Zeming , Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Papua New Guinea. – Opening address by Niwat Sutemechaikul, Director General, Department of Fisheries, Thailand – INFOFISH Appreciation 09.45 – 10.00 Tour of Exhibition 10.00 – 10.30 Coffee break / Press conference 10.30 – 11.00 Keynote address by Conference Chairperson, Renato Curto, President and CEO of Tri Marine Group, USA

Session I: Global Supply and International Trade

11.00 – 11.20 Global review : Supply & trade trends and outlook, Audun Lem, Chief, Products, Trade and Marketing Branch, FIP, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Italy. Regional review on supply, stocks and effectiveness of the management measures 11.20 – 11.40 Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO),Glenn Hurry, Executive Director Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission WCPFC),Micronesia. 11.40 – 12.00 Indian Ocean, Rondolph Payet, Executive Secretary, (IOTC), Seychelles. 12.00 – 12.20 Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO), Michael Hinton, IATTC, USA. 12.20 – 12.45 Panel discussion. 12.45 – 14.00 Lunch Break Industry efforts towards sustainable tuna industry 14.00 – 14.20 The tuna industry’s initiatives towards sustainable tuna - Susan Jackson, President, International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF),USA. 14.20 – 14.40 Increased Demand for Sustainably and Equitably Caught Pole and Line Tuna – Emily Howgate, Programme Director, The International Pole and Line Foundation (IPNLF), UK. 14.40 – 15.00 PNA’s efforts, achievement and challenges in developing sustainable tuna industry, Transform Aqorau, Chief Executive Officer, Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) Office, Marshall Islands. 15.00 – 15.30 Panel discussion. 15.30 – 16.00 Cofee Break

Session II: Industry Status and Update

16.00 – 16.20 Japanese tuna purse seine fishing industry - new challenges and prospects, Akira Nakamae, President, Kaimaki, Japan.16.20 – 16.40 Korean tuna industry – current status, new challenges and prospects, Kwang Se-Lee, Executive Director, Silla, Co. Ltd., South Korea. 16.40 – 17.00 European Tuna Fishing Industry - Current status, new challenges and prospects for international cooperation, Julio Moron, Managing Director, Opagac, Spain. 17.00 – 17.30 Panel discussion. 19.00 – 21.00 Cocktail Reception – Hosted by Thai Tuna Industry Association (Click here for more detail)

Thursday, 22 May, 2014 (Day 2)

Session III: Global and regional tuna trade and markets

09.00 – 09.20 The US and North American canned tuna market, Dave F Melbourne, Senior Vice President, Bumble Bee, USA. 09.20 – 09.40 The US market for fresh and frozen tuna, Mike Walsh, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Orca Bay Seafoods Inc.,USA. 09.40 – 10.00 European Tuna Industry and market - Current status, new challenges and prospects, Juan M Vieites Baptista de Sousa,President of Eurothon and General Secretary, ANFACO-CECOPESCA, Spain. 10.00 – 10.30 Panel Discussion 10.30 – 11.00 Coffee Break 11.00 – 11.20 The Two Latin Americas - Pacific vs Atlantic : Potential impacts on the dynamics & challenges of the tuna industry, Dario Chemerinski, Country Manager Brazil & Emerging Markets Exports Manager, Costa d'Oro S.p.A, Brazil. 11.20 – 11.40 Japanese Tuna Industry Market: Hidenao Watanabe, Director, Overseas Fisheries Cooperation Office, Japan. 11.40 – 12.00 Asian Tuna Trade, Fatima Ferdouse, Chief, Trade Promotion Division, INFOFISH, Malaysia. 12.00 – 12.20 The impacts of sustainability factors on the marketing of tuna products in Europe, Luciano Pirovano, International Marketing and CSR Director, Bolton Alimentari, Italy. 12.20 – 12.40 The Middle East and North African Markets for Canned Tuna, Adel Fahmy, General Manager & Arnab Seguptra, Trading Director, Gulf Food Industries, UAE. 12.40 – 13.00 Panel Discussion 13.00 – 14.00 Lunch Break Market Access 14.00 – 14.25 Why does development of MSC certified tuna still lacks behind other wild seafood segments?, Henk Brus, Managing Director, Pacifical C V, The Netherlands. 14.25 – 14.50 Regulatory market access issues in the tuna trade and the value of data, Francisco Blaha, International Fisheries Advisor, New Zealand. 14.50 – 15.15 The New EU GSP and tuna trade: Jerome Broche, Fish Team Leader, DG Trade, EU Commission, Belgium. 15.15 – 15.35 Thai tuna industry – The new challenges,Chanintr Chalisarapong, President, Thai Tuna Industry Association (TTIA), Thailand. 15.35 – 15.55 Mexico - Luis Fletcher, representative of the National Commission for Fisheries and Aquaculture (CONAPESCA) at the Mexican embassy in Washington, USA. 15.55 – 16.30 Panel Discussion 16.30 – 17.00 Screening of "Saving our Tuna" film produced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Arrowhead Films for Discovery Channel Asia. Introduction remark by Gordon Johnson, Regional Practice Leader for Environment and Energy for UNDP. 17.00 Cofee break

Friday, 23 May, 2014 (Day 3)

Session IV: Sustainability, environment and Eco-labeling in the tuna industry09.00 – 09.20 Cost and benefits of the MSC certification programme in the tuna industry, Bill Holden, MSC Pacific Fisheries Manager, Australia. 09.20 – 09.40 Cost and benefits of the FOS’s certification programme in the tuna industry, Paolo Bray, Director, Friend of the Sea, Italy 09.40 – 10.00 Cost and benefits of the Earth Islands Institute Dolphin Safe Tuna Certification Programme, David Phillips, Executive Director, Earth Island Institute (EII), USA. 10.00 – 10.20 Cost and benefits of Marine Eco-label Japan (MEL), Masashi Nishimura, Chief, Resources Management Office, Japan Fisheries Association, Japan 10.20 – 10.45 Panel Discussion 10.45 – 11.15 Coffee Break 11.15 – 11.35 WWF’s views on eco-labelling and sustainability of the tuna industry, William Fox, Vice President, Fisheries, WWF, USA/p> 11.35 – 12.00 The impact of Ecolabelling to fish stocks, fishermen and consumers, by Eugene Lapointe, President, IWMC, World Conservation Trust, USA. 12.00 – 12.20 PEW’s view on Eco-labelling and sustainability of the tuna industry, Amanda Nickson, Director, Global Tuna Conservation, The Pew Environment Group, USA. 12.20 – 12.40 Greenpeace (Casson Trenor, Senior Ocean Campaigner, Greenpeace USA) 12.40 – 13.00 Panel Discussion 13.00 – 13.15 Wrap up and closing 13.15 – 14.00 Lunch Break |

Million-Dollar Fish

Sushinomics: How Bluefin Tuna Became a

Once used for cat food, the endangered fish is now one of the most prized delicacies in the world.

In 2013, Kiyoshi Kimura, the owner of a Japanese sushi restaurant chain, paid $1.76 million for the first bluefin at Tsukiji, which weighed 489 pounds. Kimura had paid $736,000—a world-record price at the time—for the first tuna of 2012. That fish weighed 593 pounds.

It's no surprise, then, that journalists were steeling themselves for what was sure to come on January 4, 2014: If the past decade's trend in pricing continued, this year's first tuna would surely fetch more than a million dollars. But the Tsukiji fish market bucked tradition this weekend and sold its first tuna to Kimura, yet again, for a mere $70,000. That's still way more money than most bluefin go for in Japan. But compared to what everyone was expecting—an extravagant sum to start off the new year and remind us that these are the most prized fish in the sea—that's one crazy cheap tuna.

Andrew David Thaler, who writes about the ocean on his blog Southern Fried Science, had this to say about the many factors at play in the Tsukiji auction last January:

I’m certain that we’ll see this number presented as an argument against bluefin tuna fishing, as an example of an industry out-of-control, and as a symbol of how ruthlessly we'll hunt the last few members of a species to put on our dinner plates. These issues are reflected in the tuna market, but I want to urge caution in drawing too many conclusions from this record breaking number.What should we make of the dramatic nosedive in bluefin bidding at this year's auction? To answer that, we need to understand how this species rose to such prestige in the first place.

There are several issues in play at the first tuna auction of the year, and only some of them relate to the tuna fishery. Among the patrons of the Tsukiji fish auction, it is considered an honor to buy the first bluefin of the new years, and bidding wars reflect this fight for status. The massive international headlines that follow the purchase of such a fish is free advertising for the winner. As many auction-goers know, landing a high, early win is a way of marking your territory and letting your competitors know that you have the bankroll to push them out of a bidding war.

If $1.8 million is actually what this fish is worth to the consumer, it would sell for a hefty $345 at the dinner table, minimum. The owner, Kiyoshi Kimura, reports that the tuna will be sold at a huge loss–about $4.60 per serving.

All three species of bluefin tuna are currently overfished, and over the last few years attempts to protect bluefin tuna have been thwarted by fishing interests in Japan, New Zealand, the United States, and Mediterranean countries, among others. While this record breaking sale should serve a clarion call for increased scrutiny of the global tuna trade, it does not accurately reflect the market value of the fish.