Japan is largest fish-eating nation in the world, consuming 7.5 billion tons of fish a year, or about 10 percent of the world's catch. This is the equivalent of 30 kilograms a year per person. Their nearest rivals the Scandinavians consume only around 15 kilograms per person. The Japanese consume so much fish that Japan has traditionally controlled the world prices for seafood with it huge demand.

Japan is home to a $14 billion commercial fishing industry. Fish and a variety of other sea creatures are caught by local fishermen, imported and raised in aqua farms. There are around 200,000 fishing vessels in Japan. Of these about 2,000 fish for tuna and bonito. <

Sixty-six percent of the fish consumed in Japan is domestically caught. Even so Japan relies on imports for about half of its annual consumption of seafood, about 7.2 million tons in 2008.

Japan and China are the largest fishing nations. By some measures China has surpassed Japan in recent years but most of the fish that the Chinese consume are freshwater fish raised in fish farms. The Japanese eat mostly sea fish.

By other measures Japan is still the largest fishing nation. According to a National Geographic survey the largest harvesters of fish (metric tons) were: 1) Japan (7.5 million); 2) China (7 million); 3) Peru (6.7 million); 4) Chile (6.5 million); 5) Russia (5.2 million); 6) the U.S. (5 million).

Still the Japanese fishing industry is on the decline. Japan caught 12.8 million tons of fish in 1984 but only 6.35 million tons in 2000 and 5.52 million tons in 2002. In 2000, it imported 3.54 million tons of fish, double what it imported in 1984.

Fish consumption dropped around 15 percent in the 1990s, largely because of the time and difficulty in preparing it. The number of fishmongers in Tokyo declined 53 percent to 1,130 between 1980 and 2000.

Fish were traditionally used to fertilize rice fields and today symbolize the hope of an abundant harvest.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website:

Links in this Website: FISHING IN JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISHING AND JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TSUKIJI FISH MARKET IN TOKYO

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TRADITIONAL FISHING IN JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PEARLS AND JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SEAFOOD IN JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUSHI

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUGU (BLOWFISH) IN JAPAN

Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Good Websites and Sources on Fishing:

Good Websites and Sources on Fishing: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive

japan-photo.de ; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

maff.go.jp/e ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Fisheries Section

stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition

stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News

stat.go.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Blue Fin Tuna Fishing :

Good Websites and Sources on Blue Fin Tuna Fishing : Northern Blue Fin Tuna

fishbase.org ; Southern Blue Fin Tuna

fishbase.org ; Wikipedia article on Blue Fin Tuna

Wikipedia ; Blue fin Tuna Fishing Methods

content.cdlib.org ; Mediterranean Blue Fin Tuna Aquaculture

eeuropeanrussianaffairs.suite101.com ; Southern Bluefin Tuna Aquaculture

sardi.sa.gov.au/aquaculture ; Blue Fin Tuna Farming Off Spain

uni-duesseldorf.de

Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo :

Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo : Tsukiji Market site

tsukiji-market.or.jp ; Essay on Tsukiji

aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia

Wikipedia ; Tsukiji Research

people.fas.harvard.edu ; Japan Guide

japan-guide.com Getting There: Best Japanese Sushi

google.com/site/bestjapanesesushi ;

Photos: Tsukiji Tour http://homepage3.nifty.com/tokyoworks/TsukijiTour/TsukijiTourEng.htm

Traditional Fishing in Japan:

Traditional Fishing in Japan: Ama Divers

thingsasian.com ; Ama Physiology

archive.rubicon-foundation.org ; Amasan

hanamiweb.com ; Squid Fishing

jtackle.info/squid ;

Cormorant fishing Wikipedia article

Wikipedia ; Cormorant fishing in Yangshuo

yangshuo-travel-guide ; Photos of Cormorant fishing

molon.de ; Articles on Cormorant Fishing

highbeam.com

Globalization and Fish Imports in Japan

Growing global demand for fish is hurting Japan’s haul. Countries that used to catch large amounts of fish and export it to Japan are now keeping the fish for themselves.

Japan has become increasingly reliant on imported fish as fish stocks in its territorial waters have declined and the price of imported fish had dropped making it an attractive alternative to locally-caught fish.

Japan’s seafood self sufficiency rate has declined from a peak of 113 percent in 1964 to 59 percent in 2006. Tuna, salmon and shrimp are among the most widely consumed seafoods. They are mostly imported.

Worried about supplies and high prices, the Japanese government is urging people to eat more locally-caught fish to reduce Japan’s dependance on imported fish and especially encouraging people to eat seasonal fish—such as bonito in the spring, squid and saury the autumn and yellowtail snapper in the summer—whose catches are usually abundant.

Cheap imports has brought down the prices of many fish in Japan. The price of bigeye tuna is about ¥1,500 a kilogram, half of what it was in the 1980s, due mainly to cheap imports from Taiwan.

Fish Catches in Japan

Fish stocks in Japan’s territorial waters are declining. Data shows that the stocks of 48 percent Of 90 categories of shore fish caught off Japan in 2007 have declined. Many fishing villages have go belly up and lost of the majority of their residents.

The catch of yellowtail snapper off Toyama Prefecture in winner of 2009-2010 was only one tenth of the catch in a usual year. Yellowtail caught cold water are favored because of their high fat content. Warmer sea waters were partly blamed for the low catch.

Top 5 most caught fishes (millions of tons per year): 1) Alaska Pollack (4.5); 2) Japanese Pilchard (4); 3) Chilean Pilchard (3.25); 4) Atlantic Cod (2.25); 5) Chilean Jack Mackerel.

Of all the fish caught in the world. Only about three quarters are eaten by humans. The remainder are used to make things like glue, soap, pet food and fertilizer.

Surmami, a protein past that is processed into seafood products such as fake crab, is made from pollack, a fish caught in huge nets large enough to swallow the Statue of Liberty and processed in huge floating factor trawlers

In 2007, trawlers based in Kesennuma Port in Miyagi Prefecture caught 34,900 tons of saury, the forth largest amount ever netted by a Japanese fleet. Fishermen sold the fish for around 40 cents a kilogram.

Japan’s Fishing Agency hopes to increase fish stocks by building 40-meter-high, 200-meter-long artificial underwater reefs from blocks made of coal ash and concrete to attract anchovies, horse mackerel.

Japanese Fish Industry

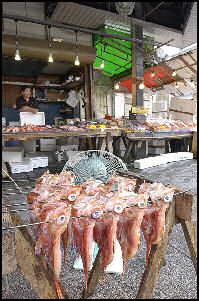

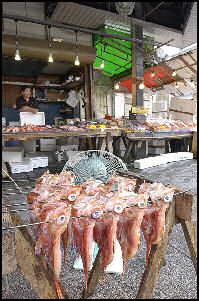

squid spinning

The fish industry in Japan includes fishermen, traders, purchaser of fish, air shipping companies, trucking companies, butchers, packagers, delivery people. On its journey from the sea to customers plate, a single fish can change hands a dozen times, with each business taking a profit and adding an expense.

As Japan became more affluent in the 1980s the price of bluefin tuna soared. Worried that fisheries could be quickly overfished, regulators tried to impose quotas

The fishing industry has enormous political clout. They are strong supporters of the LDP, the political party that has ruled Japan during most of the post-war period.

Fishing vessels in Japan (1996): 354,000 in 2,950 fishing ports. Fishing employed 270,000 people in 1998, compared to 478,000 in 1978.

About 90 of the fishing on the open seas is done by vessels from Japan, Poland, Russia, South Korea, China, Spain and Fishing vessels from these countries range across all of the world oceans. They are sometimes found poaching in waters off Senegal, Argentina, Gambia, Ghana, Indonesia and the Philippines.

The Japanese use huge floating processor that not only catch the fish but package and freeze them for the Japanese market.

Problems in the Japanese Fishing Industry

The fishing industry in Japan is facing many of the same problems as farming. A decline in incomes, empty towns and an aging work population. Suvendrini Kakuchi wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Low counts of other fish, along with a dwindling, aging group of fishermen — the average age is now over 60 and their numbers are shrinking an average of 5 percent a year — have threatened the industry and the livelihoods of those who depend on it.” [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

“The Fisheries Agency of Japan said the market for domestic fish in 2008 dropped to $11.7 billion, down more than one-third from $18.8 billion a decade earlier, based on current exchange rates. The agency also has warned that half of the marine resources in the waters surrounding Japan have dropped drastically in the last two decades. “ [Ibid]

Overfishing and Global Warning and Japan

Overfishing is becoming a serious a problem in Japan. Overfishing in coastal areas has have depleted catches and caused fishing villages to shrink to edge of disappearing. Cod has been fished out in many places and salmon, saury, cuttlefish and crab are much scarcer than they used to be.

Suvendrini Kakuchi wrote in the Los Angeles Times, the Fisheries Agency of Japan “has warned that half of the marine resources in the waters surrounding Japan have dropped drastically in the last two decades. For example, less than 20,000 tons of horse mackerel, a fish widely eaten because of its affordable prices, is caught annually, down from 70,000 tons in 1991. And Pacific saury, a fall delicacy, is now fetching as much as $8 a fish — eight times as much as two years ago. The government agency attributed the low catches to rising sea temperatures that are affecting spawning and growth of fish and to overfishing.” [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

Overfishing is becoming such a problem that fish that have been traditionally been regarded unwanted are now big given a second look and turned into various food products. For example, small lizardfish, small horse mackerel, young yellowtail, deep-sea fish, dorado, Japanese butterfish and small blue mackerel, which in the past were thrown out, abr now being pressed into things like fish paste, fish sausages, skewered fish balls, and fish burgers.

Lower catches have led to an overwhelming dependency on expensive fish farms and imports, driving up costs.

Record hawls of shirasu whitebait caught off Fukushima Prefecture in the summer of 2010, the large catch was attributed to warmer waters associated with global warming. Other areas recorded lower than usual caches.

Reforming the Japanese Fishing Industry

Hiroyuki Matsuda, an eel resource researcher at Yokohama National University, told the Los Angeles Times there is no time to lose in instituting major changes to help the Japanese fishing industry survive, and the government needs to lead the way. "There must be a fundamental change in thinking," he said, pointing to the need for a fishing policy based on developing grass-roots-level sustainable fisheries. Takuhira Kaneko, head of Act For, a Fukuoka marine product wholesaler, agrees. "We need new policies from the government to help us protect resources that can even include cutting down on catches" over the long term, he said. [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

Seven years ago, Act For started the Mottainai fish project to buy fish discarded from those caught in nets and use them in such products as fish cakes. Mottainai, whose name means "stop wasting," accounted for $20,000 in sales last year and "helped us to face a business slump due to decreasing catches of popular fish," Kaneko said. [Ibid]

Wakao Hanaokoa, a tuna expert at environmental group Greenpeace Japan, has called on the government to develop a fishing management system to track endangered species "as a means of ensuring catches are from sustainable sources." Such a system, he told the Los Angeles Times would keep supplies limited and restrict the selling of endangered species, two important steps to protect them.” [Ibid]

Most fishing industry experts' say the that fish farming is the best solution for now.

Local government in some places are teaching students and teachers about fish caught in their areas and serving the fish in school lunches as part of an effort to help preserve fish-eating cultures peculiar to the areas. Among the fish being protected are flying fish and sailfin sandfish.

Resistance to Reforming the Fishing Industry in Japan

Japan’s resistance to seriously tackle the overfishing problem are manifested its reluctance to give up its controversial whaling program harvests about 1,000 whales a year. Tokyo justified the practice by saying the eating of whale meat is a tradition that must be protected. Japan also faced intense international pressure over fishing for young bluefin tuna in the Pacific, where its catches of 18,000 tons two years ago amounted to 90 percent of the total. At a March meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, the Japanese delegation fiercely opposed a proposed ban, which was defeated. Conservationists saw the effort as a means to protect the lucrative sushi market. [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

Akihiro Ono, a researcher at the Nihon Yoshoku newspaper, said Japan was trying to balance its responsibility to replenish fish stocks with its need to protect the nation's traditional marine-based diet. "The government hopes to continue with measures that will pave the way for sustainable fish catches. Accepting fishing bans is only the last resort," he said.

Fish Farming in Japan

stockig salmon in Aomori

Japan is one of the world’s top fish farming countries. Statistics show that the aquaculture industry produced ¥409.5 billion worth of marine products in 2009. The amount of fish raised on Japanese fish farms rose from 20.8 million tons in 1994 to 33.3 million tons in 1999. [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

Yellowtail, salmon, saurel, red sea bream and fugu (puffer fish) are the main fish raised in ocean fish farms in Japan. Sometimes they are fed tuna waste solids. Fishermen in various coastal regions raise various species, including white salmon, red sea bream and yellowtail. Hokkaido's industry produces products such as scallops, sea urchin and kelp. In Mie Prefecture, farms cultivate pearls and red sea bream while farms in Kochi Prefecture raise yellowtail and other marine products.New varieties being raised include filefish, masaba (a kind of mackerel), grunt, scorpionfish and gopher fish. Eels are raised in fresh water lakes.

Flounder have been successfully raised in swimming-pool-size tanks in Japan miles from the sea. Flounder are ideal for inland farming because they are profitable and they grow well in tanks because they don't move much. For other species the cost of building tanks is prohibitively expensive.

A former construction industry manager has been able to harvest caviar from sturgeon he has grown from fry in tanks on the banks of a river in Agano in Saitama prefecture near Tokyo. Most of the caviar is served at his restaurant.

Carp farming is believed to have originated on the Yayoi period (400 B.C.-A.D. 300). The conclusion is based on the discovery of fossils of young carp teeth at an archeological site near Nagoya in what appears to have been a moat. Tsuneo Nakajima, the curator of the Lake Biwa Museum, which contains the fossils, told Kyodo, “The Yayoi may have released carp into rice fields, moats or ponds during the spawning season and the fish produced eggs. Primitive farming probably started in this way.”

The young carp teeth were found in a different place than adult teeth. It is unlikely the two groups occurred in separation like this naturally and thus suggests fish farming. The technology for fish farming is believed to have been introduced from China along with rice farming,

Low Eel Catches and Eel Farms in Japan

Suvendrini Kakuchi wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Dramatically lower eel catches from local river habitats have led to an overwhelming dependency on expensive fish farms and imports, forcing restaurants like Takayasu's out of business.” In 2009, “eelers caught 267 tons from natural habitats, a drop of two-thirds from the amount caught a decade earlier, according to the Nihon Yoshoku Shinbun, a publication that tracks marine resources. Last year's catch was less than 1 percent of the nearly 35,000 tons consumed; farming provided nearly 11,000 tons, and imports from China and Taiwan accounted for the remainder, the publication said.” [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2010]

Industry experts have criticized the quality of imports as uneven and have noted that cultivating eels on about 300 fish farms nationwide is a high-risk, labor-intensive venture."The sad story of Japanese unagi is just one of the many examples of how Japan's voracious appetite for fish has created problems for itself," said Hiroyuki Matsuda, eel resource researcher at Yokohama National University. [Ibid]

Key progress was made in an aquaculture venture at Mie University that successfully raised eels from eggs, the first such experiment in the world. Still, it would take some time before growing eels from eggs could be turned into a commercial venture. Artificial feed and other expenses would make each eel cost thousands of dollars, experts said.

Michimasu Takayasu, fifth-generation restaurant owner, told the Los Angeles Times he worries about the growing expense. His Chuhei Co. is famous for the Bando taro variety of eel, a local species savored for its succulent meat but no longer found in local rivers. The eels are cultivated on expensive natural fish feed at two breeding farms in Japan, and annual harvests amounting to about 60 tons are sold to top restaurants in Tokyo. "Very soon, eating at special eel restaurants like ours might be only for the very rich," Takayasu said. "That's not going to do us any good."

See Unagi, Food, Life

Japanese Fishermen

Less than 1 percent of the Japanese workforce make their living in fishing. Large fishing fleets have exhausted most of the fish supplies near the coast.

In many places fishermen are dependent on part time work linked with public work projects to make ends meet. A member of fisherman’s cooperative told the New York Times, "Historically, we are all dependant on the government and ruling party for handouts."

Fishermen routinely visit shrines to pray for safety. When a boat is launched it is given a special ceremony. Many towns have a Shinto shrine dedicated to Ebitsu, one of the seven lucky gods and the patron of fishermen. Prayers are said for good catches, good weather and safe passages at sea. Festivals feature fishermen carrying portable shrines with Ebitsu on them.

The Japanese have been fishermen for a long time. Six-thousand-year-old Jomon period sites have yielded fish hooks, net sinkers, spears and dugout canoes. Around 5,000 small fishing villages still freckle the coastline. This works out to about one for every four miles of coastline.

Tairobata—fishermen’s flags—used to be hoisted to announce bountiful catches. Now they are used mainly to launch ceremonies and festivals.

Japanese Fishing Villages

fishing festival

In traditional fishing communities the vessels are mostly owner-operated. Some ships have enclosed cabins and inboard motors but most are just open skiffs with outboard motors. Concrete breakwater provide a safe anchorage for vessels in the community. Houses are packed around the cove.

Most coastal fishing is still done from small, owner-operated family vessels. Strict fishing rights laws prevent large vessels from working on inshore waters. Villages have the rights to harvest sea urchins, abalone, clams and spiny lobsters in waters adjacent to their communities.

Many Japanese fishermen are getting old. Many fishing towns are emptying and becoming ghost towns. Many local fishing industries are expected to close down when the last batch of fishermen retire.

Foreign Workers in Japanese Fishing

Japanese boats that spend long periods of time at sea rely on foreign workers, many of them from Indonesia. Many get paid less than the minimum wage for foreign workers of $375 a month. Sometimes they are paid considerably less than that. One Indonesian seaman told the Yomiuri Shimbun the most he was paid was $280 a month. “Sometimes, I’m only paid $150,” he said. Most are hired by brokers in their home country and presumably some of their pay goes to them.

Not only are foreign fishermen poorly paid, they also work like dogs. One told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “I slept only three to four hours a day. It was grueling work with no breaks. The toughest part was constantly being tossed about in a narrow cabin by waves for four to six weeks.”

Some of foreign workers come to Japan as trainees and are paid around $1,000 a month during their training period but their pay drops to between $300 to $700 a month, including overtime, when they start working as seamen. Many find the work to difficult and run away. Some flee their boats in Japan and find better paying jobs.

Dangers Faced by Japanese Fishermen

Every few months or so some fishermen go missing after their boat capsizes in rough seas or die when their boat collides with another vessel in Japan’s busy coastal waters. In September 2007, four fisherman went missing after their boats capsized off Kinkazan island in Miyagi Prefecture in southern Kyushu when winds picked up to 36 kph and waves were four meters in height. In April 2008, eight people died when their scallop-fishing boat sunk in rough seas off Aomori in northern Honshu.

In April 2004, three of four crew members aboard of South Korean fishing docked in the port of Oda were found dead, asphyxiated by a gas created by rotting squid guts slated to be used in a salted snack. The three men were found in sections of the ship where the guts were kept.

In September 2005, seven of eight fishermen were killed on 19-ton saury fishing vessel that capsized off of Nemuro, Hokkaido after it was struck by a 41,507-ton large Israeli-flagged container ship.

In December 2003, four died when a fishing boat sank off Shimane Prefecture. The 80-ton ship with a 10-man crew ran aground on a shoal and was overturned and sunk because of large waves and strong winds The surviving crew members were rescued clinging to rocks.

In October 2008, three fishermen were killed when a 14.75-ton fishing boat with six fishermen on board and a 9,813-ton cargo ship collided about 1.8 kilometers south of Minna Island in Okinawa Prefecture. All six of the fishermen were thrown into the water.

On April 2008, twelve of the 22 crew member aboard a Japanese fishing boat went missing after their 135-tom vessel capsized and sank off Hiradojima Island, Nagasaki.

In May 2009, a tuna boat caught fire and the crew had o abandon ship. Four people were initially reported missing. One was found dead, Another was found alive in a life raft. Two others were never found.

In October 2009, three men were rescued at sea after spending three days in an upside down capsized boat in seas off Hachijojima island. The men huddled in a small air pocket in a compartment of the 19-ton boat after it was capsized by waves from a typhoon. One survivor told Kyodo, “I was wondering inside the boat how I’d die. And it felt horrible to think about when I might stop breathing.” The three men had little to eat and shared a small amount of water. They were very hungry and slightly dehydrated when they were rescued by the Japanese coast guard. Five other crew men on the boat died.

In 2008, fisherman in Surga Bay began wearing life jackets after a series of fatal boat accidents left five people dead.

In January 2008, a 55-year-old fisherman was rescued after treading water for 15 hours after his boat capsized off Miyakojima Island in Okinawa Prefecture

In July 2011, Kyodo reported that a 70-year-old fisherman adrift for 20 days was found safe by the Japan Coast Guard. Ryoko Shimabukuro, of Ie, Okinawa Prefecture, was found aboard the boat drifting off Cape Muroto, Kochi Prefecture, following a report sent by a foreign vessel to the 5th Regional Coast Guard Headquarters in Kobe. Shimabukuro appeared to be in good health and said his boat had encountered engine trouble, officials said. According to the fishing cooperative in his village, Shimabukuro left port June 8 and planned to return after around 10 days. He was last seen off Cape Hedo, Okinawa, on the evening of June 10. [Source: Kyodo, July 1 2011]

Japanese Fishing Boats in Russian Waters

The Kuril Islands boast rich fisheries, with salmon, flounder, tuna, shrimp, clams, crab, kelp and sea urchins. A third of Russia's fish catch comes from the greater island region. The catch from the Kurils is worth over $1 billion a year.

Japanese fishermen who fish in waters off the islands do so at a high risk. Dozens of Japanese fisherman have been jailed for poaching and broaching Russian territorial waters. Russian border-patrol ships have injured fishermen and shot at and damaged Japanese vessels accused of fishing in Russia-claimed waters off the Kuril Islands.

Russian border-patrol ships have injured fishermen and shot at and damaged Japanese vessels accused of fishing in Russia-claimed waters off the Kuril Islands. Between the end of World War II and 2004, 1,330 Japanese fishing boats were captured by Russian patrol boars. In these incidents there has been only one fatality, in 1956.

In August 2006, a Russian Border Coast Guard patrol ship opened fire on a Japanese crabbing vessel, killing a fishermen, near Kalgarajima island,—part of the disputed Russian-controlled Kuril Islands territory. The captain and two crew members on the Japanese boat were taken into custody by the Russians. According to the Russians the Japanese were warned with flares and told to stop. The Russians said they only deciding to open fire—with machine guns from an inflatable boat—because the vessel tried to escape. Crew members taken into custody were freed a after a couple weeks. The captain was detained for seven weeks and released.

In June 2007, Russia seized a Japanese fishing boat that had permission to fish in Russian waters because it was carrying more fish than it was allowed and an expensive kind of salmon was falsely listed as a cheaper kind.

In December 2007, four Japanese fishing boats were seized off Kunashira Island in the Kurile Islands. The crew members were released a couple of months later

In January 2009, 10 fishermen in crab-fishing boat were arrested by Russian authorities waters on charges of poaching in Russia’s exclusive economic zone. The boat apparently drifted into the Russian zone while the fishermen were sleeping. The fishermen were released about week later after the payment of $140,000 by the firm that employed the fishermen. See Government, International, Russia, Kurile Islands

Fishing and Fuel Costs in Japan

Soaring fuel costs have severely hurt the fishing industry. The further the vessels go out to sea, the more fuel they use, and the higher their cost are. Particularly hard hit are tuna boats which travel to distant areas and spend months at sea.

The cost of heavy fuel oil, the main fuel for fishing vessel, rose from about ¥39,000 per kiloliter n 2003 to ¥69,000 in 2007 to ¥105,000 in June 2008. Trawlers that operated in seas off Japan did everything they could to cut costs: operating their boats at lower speeds and using fewer fish luring lights, but still found their annual cost were about $50,000 higher than previous years.

Many fishermen were forced to stop working or scale back their operations. An estimated 40 percent of fishing operations faced bankruptcy. In June 2008, tuna fish boat operators in Japan, China, South Korea announced the were going to suspend operations for several months because of rising fuel costs. Because quotas for bluefin had already been met the ruling was expected to mostly effect fishing for bigeye and yellowfin tuna. Earlier in the month squid fisherman suspended work to draw attention to high fuel prices.

On one day in July 2008, 200,000 fishing boats— nearly all those operating in Japan—suspended operations to bring attention to their plight and seek government help.

Huge Jellyfish Off Japan

Echizen jellyfish—nasty creatures that can weigh up to 200 kilograms and reach a size of two meters in diameter—have caused havok in the Japanese fishing industry, particularly in the Sea of Japan off of Fukui, Shimane and Ishikawa Prefecture in western Honshu. The jellyfish have brown poisonous tentacles that kill fish and cause them to lose their color. Their huge numbers spoils fish catch and fouls fishing nets with a nasty smell. Their massive weight tears the nets when they are pulled out of the water.

The damage to the fishing industry has been in the tens of billions of yen. On fisherman told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The nets were fouled by hundreds of jellyfish as soon as they were put out. There was little room for other fish, The fish that touched the tentacles of the jellyfish turned white, and the retail value of the fish is reduced to zero.” The presence of the poisonous jellyfish has been particularly devastating to the fishing for cavalla and yellowtail because these fish stay well clear of the jellyfish.

The jellyfish population explosions have been blamed on global warming, increased nutrients in the water, and overfishing of jellyfish competitors. In the old days Echizen jellyfish disappeared by the time the autumn fishing season peaked. But warmer waters, perhaps caused by global warming, have caused the jellyfish to stick around longer than in the past. Some blame China for the problem, saying the jellyfish originate in waters off the coast China and their growth has been triggered by pollutants dumped in the sea.

To combat the jellyfish problem the Japanese government has set up observation stations and provided forecasts for jellyfish invasions. Boats carry nets outfit with special blades that cut the jellyfish into little

People are also trying to come up with uses for Echizen jellyfish. An aquarium in Yamagata Prefecture sells a variety of Echizen jellyfish, including an ice cream containing diced jellyfish. Researchers have found that protein extracted from the jellyfish helps joint cartilage grow,.

Giant Jellyfish Migrations

The large jellyfish have appeared every year since 2002. Before that they showed up once every few decades. They originate in waters off the coast of China in the Yellow and Bohai Seas and migrate past South Korea to southern Japan. They get their Japanese name Echizen kurage after Echizen, the old name for a port in Fukui Prefecture, where the jellyfish were spotted.

In 2005—a particularly bad year—an estimated 300 million to 500 million Echizen jellyfish passed into the Sea of Japan through Tsushima Strait and spread to the Pacific and were found in most coastal areas of Japan.. In some place the sea was literally engulfed in them. More than 100,000 complaints about giant jellyfish were lodged, mostly damaged nets and lost fishing time. In 2006 huge masses of Echizen jellyfish appeared in the Sea of Japan after a typhoon passed through the region in mid September,

The worst infestation of Nomura’s jellyfish in four years was witnessed in 2009. What was usual about that year was that for the first time the jellyfish made it to the Pacific from the Sea of Japan through the Tsugaru Strait between Hokkaido and Honshu and from there migrated south, making it Tokyo four months after first appearing off the west coat of Kyushu. In Chiba a fishing boat overturned from he weight of trying to lift a net full of jellyfish out of the water.

Some scientists blame overfishing and global warming for the jellyfish swarms. Prof. Shinichi Ue, an expert on the jellyfish at Hiroshima University, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Humans have brought about abnormalities in the marine eco-systems that can no longer be corrected...As mall fish and fry of large fish have fallen in number, creatures that prey on Echizen jellyfish, which eat zooplankton, also have decreased.

When the jellyfish polyps are developing they sometimes leave “legs”—podocysts which can develop into jellyfish—on rocks that lie dormant when the water is relatively cool. When the water temperature rises above a certain level the “legs” can develop into polyps and then become jellyfish. Dr. Toru Yasuda, an expert on the jellyfish at Fukui University, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The rise in water temperature might have encouraged podocysts to sprout and polyps to grow.”

Japanese scientist have asked Chinese scientists to cooperate with them in a study of jellyfish, focusing on the mouth of the Yangtze River, measuring the water quality and temperatures amd other variables and see if these provide clues to how the jellyfish evolve.

Japan and International Fishing Laws

Japan has ignored international fish quotas on whales and blue fin tuna and refused to sign international fishing treaties.

Japan has traditionally been a major advocate of “fishing freedom.” Although it ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea—which states that nation obliged to cooperate with control of “highly migratory” fish such as tuna Japan has not been very active in fish control. Until recently Japan had been unwilling to join the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement, which sets rules on fishing of certain kinds of fish but finally ratified it in 2006. In some cases Japan had boycotted and disrupted meetings aimed at establish controls on fishing in certain areas of the Pacific.

In January 2007, Kobe hosted an international conference on overfishing. The fishing industries and governments of about 80 countries participated, . On the top of the agenda was the problem of the overfishing of tuna. A plan was adopted to slow the decline of global tuna stocks by aggressively combating illegal fishing, controlling the growth of fishing fleets and sharing data on stock sizes.

Whaling, See Nature and Science, Sea

Japan has wrangled with Australia and New Zealand over quotas on the catch of southern bluefin tuna in waters near Australia and New Zealand. Currently Japan is limited to an annual catch quota of 6,000 ton plus a research-fishing catch of 1,400 tons.

See Kurile Islands Above

See Korea

Japan and Drift Nets

Japan was once one of the leading users of drift nets but stopped in 1992 under U.N. pressure.

In the 1980s it was estimated that the number of birds, marine mammals and unwanted fish killed by drift nets from Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese fishing boats far outnumbered the fish sold in markets. Some drift nets were 30 miles long and were used primarily to catch squid and tuna. Most of the other fish caught are tossed overboard. The United Nations passed a resolution that has ended a practice sometimes called "strip mining of the sea" but enforcement in the vast ocean has been difficult.

Japanese Fish Markets

See Tsukiji Fish Market, Places, Tokyo

One fish merchant told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “I know how fatty a fish is just by looking at it...Fish which grow up in fast currents...have firm meat, because they swim hard, and they are tasty because they eat a lot...The knack to finding high-quality fish is to select vigorous ones because they have to stay alive overnight, or we can’t call them fresh.”

The fish markets are changing. With the depletion of fisheries around Japan and the changing of the fish distribution system, markets are selling less Japanese fish and more foreign fish, especially those caught on Chinese, Korean and Taiwanese vessels, or flow in from the United States, Australia, Mexico or Chile.

Most fish catches are placed in tanks or packed in ice and loaded from the fishing vessels directly onto trucks that carry them to Osaka and Tokyo and other destination during the night arriving at local fish markets in the morning. More and more fish are bypassing the fish auctions. Using refrigerated trucks outfit with tanks, fish can be delivered fresh almost anywhere in Japan.

Tuna

See Separate Article for Bluefin Tuna,

Crabs and Shrimp and Japan

collecting shellfish in

the 19th century

The Japanese love crab and regard it as a wintertime treat. Many places rely on crab to attract tourist in the winter.

Most of the crabs eaten in Japan are similar to the giant king crabs caught off Alaska. The crab catch season is from October or November to April or May. It used to be longer but has been shortened as a result of declining catches. One of the best crabbing areas is in the Japan Sea 50 to 100 kilometers off the coast of Kamicho, Hyogo Prefecture. Typically 38 tons of crabs are caught there per day, with the crabs selling fo ¥25,000 to ¥30,000 per 30 kilogram box at wholesale markets.

Fishermen in Ntosuke Bay fishing for Hokkaido shrimp still use traditional

utasebune sail boats and trawl nets dropped from boats propelled by their triangular sails. The fishing is done from three dozen boats during a season that last for several weeks in June and July.

Illegal Crab Fishing in Russia and Japan

Fishing for king crab off the Kamchatka peninsula is especially lucrative. After the crabs are caught the vessels travel a few hundred miles south and sell the crabs for a lot of money in Japan. Many the ships use forged documents to clear customs. In the Kamchatka peninsula in eastern Russia, fishing permits are technically free but people have been known to pay $2.5 million for a hundred-ton quota to fish crab.

Rusted boats haul in as much as 50 tons of king crab a day from the nutrient-rich Sea of Okhotsk. After the day's catch is hauled a work force of 427 men work through the night below the deck cooking and canning the crabs for market.∞

As of 2002, before a crackdown on illegal crab fishing, Russia accounted for half of Japan’s total crab supply of 160,000 tons a year. Buyers in Japan pay between $50 and $75 per kilogram.

Japan and Illegal Crab Fishing in Russia

The Russian crab fishermen traditionally pulled into Japanese ports like Nemuro and Kushiro with forged papers, sold their catch for a huge profit, partied and bought stereos, televisions and other electronics, or maybe even a car, and returned to Russia, hopefully avoiding Russia coast guards boats whose primary duty is catching poachers and who are ordered to shoot at boats the at don’t stop..

Many of the boats involved in the illegal fishing trade are rusting heaps that lack safety equipment and sometimes working emergency radio. The men that work the boats are rough and cruel. A few have tattoos on their eyelids.

In 1998, Japan imported 70,000 tons of crab from Russia. Only 5,000 tons of that was documented on the books in Russia. In 2000, 86 ,000 tons of crab came from Russia. Only 3,000 tons of that was documented on the books in Russia.

In 2002, the Japanese government began cracking down on crab smuggling. Russian ships fully loaded with crab that lacked proper documents were tuned away from Japanese ports. Afterwards the price of crab soared in Japan by more than 50 percent, which cerated more incentive for those involved in the illegal crab trade. The Japanese crackdowns came in after Japan and Russia set up a notification system in which Russia provided Japan with prior notification of ports of calls for a its fishing oats. The crackdown also hurt the economy in the ports of call. The Russian spent a lot of money in Japan on used cars, electronics and other stuff they took back with them to Russia.

Before the crackdown the fishing boats traveled on their own directly to Japan. Afterwards they tried to outsmart authorities by loading their catch onto cargo freighters at sea and those freighters, which had proper documentation, docked at the ports. In one case the captains of a freighter and trawler were arrested after they were transferring a load of crab with Japanese waters.

The Russian sea urchin and shrimp industry operates much like the crab industry.

Fishing Bribes, Japan and Russia

In 2010, it was revealed that four Japanese companies paid Russian border guards about $6 million for tacit permission to catch walley pollack in excess their quotas. The companies were ordered to suspend operations for 70 days during the heart of the fishing season from late January to March.

Fishery executives said that bribing the Russians was a common almost expected practice. The executives said they handed cash to Russian border guards or made money transfers through Cyprus accounts and said it was a necessary part of doing business. “We did it to catch more fish than is legally allowed,” one official said.

Image Sources: 1) JNTO, Ray Kinnane, Hector Garcia, xorsyst blog, Andrew Gray Photosensibility, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various

SOUTH AFRICA

SOUTH AFRICA

Japan is largest fish-eating nation in the world, consuming 7.5 billion tons of fish a year, or about 10 percent of the world's catch. This is the equivalent of 30 kilograms a year per person. Their nearest rivals the Scandinavians consume only around 15 kilograms per person. The Japanese consume so much fish that Japan has traditionally controlled the world prices for seafood with it huge demand.

Japan is largest fish-eating nation in the world, consuming 7.5 billion tons of fish a year, or about 10 percent of the world's catch. This is the equivalent of 30 kilograms a year per person. Their nearest rivals the Scandinavians consume only around 15 kilograms per person. The Japanese consume so much fish that Japan has traditionally controlled the world prices for seafood with it huge demand.